In terms of the rules on offer and acceptance, there are two types of contracts: unilateral and bilateral.

The contract is described as being unilateral when the offeror makes a promise in exchange for the performance of a stipulated act.

In unilateral contracts only one party has obligations under the contract the other does something or refrain from something.

Acceptance of unilateral offer:

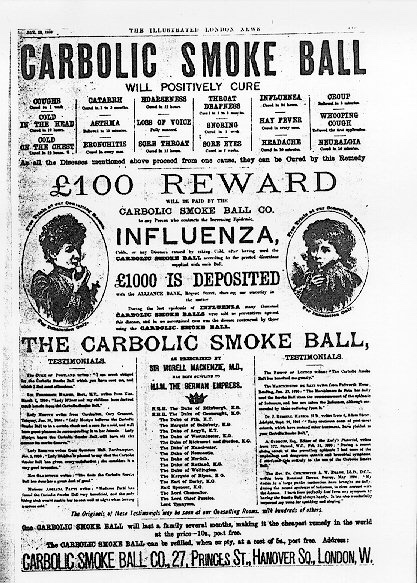

The acceptance of the unilateral offer can take place when the offeree performs the stipulated act. Once the offeree has performed the act offeror can not withdraw his/her offer. However, offeree can change his/her mind and not to continue her/his performance of a stipulated act anytime. Example in Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co. [1893] 1 QB 256 . Mrs Calill makes no promise to the Carbolic Smoke Ball to use their products and can decide not to continue her use of the smoke ball at any time.

Communication of offers in unilateral contracts:

1. In both unilateral and bilateral contracts offer must be communicated to offeree to be valid. This means that no party can be bound by an offer of which they where unaware. This proposition is supported by Gibbons v. Proctor (1891). Furthermore, the offeree must not have forgotten about the offer, and must be aware of the offer at the time of acceptance, as, decided in R v. Clarke (1927). Indeed, the American case of Williams v Carwardine (1833) 5 C. & P. 566, suggests that a contract can be arise if the offeree accept the offer (with knowledge of the offer at the time of acceptance) even though his or her motivation is directed at some other reason for action. In this case the plaintiff knew that she will die soon and gave information to the police to satisfy her conscience and not motivated by the promise of the reward. The court decided that she was entitled to the reward. She was aware of the offer of reward when giving the information and her motivation was irrelevant.

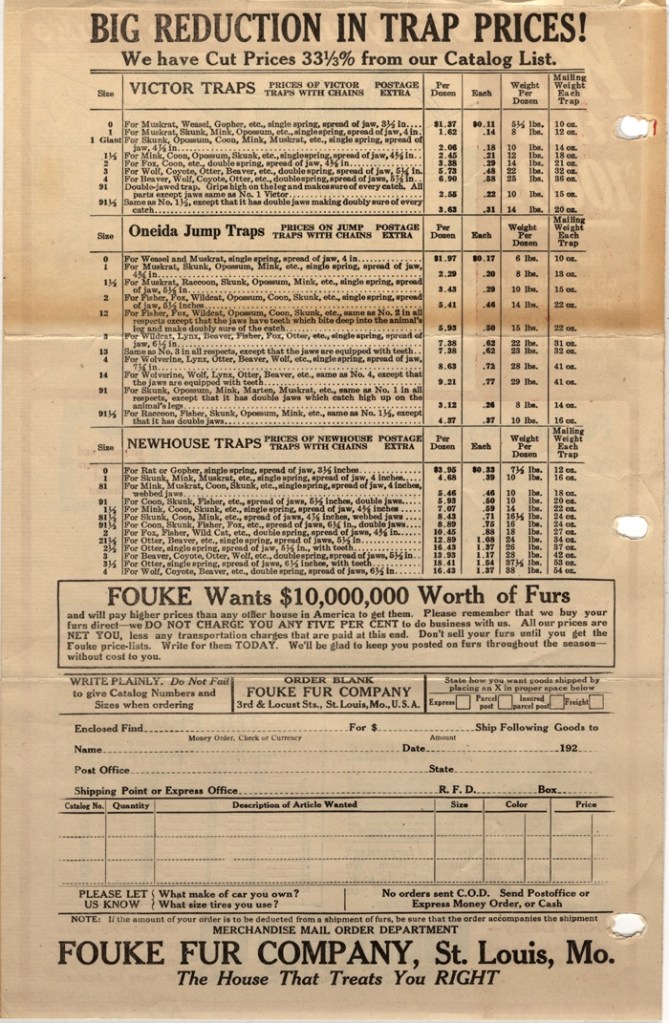

2. General rule is that revocation of an offer must be communicated to the offeree. It can be by the offeror or a trusted person whom both parties can rely (Dickinson v Dodds (1876) 2 Ch D 463. Revocation in unilateral offer is different.

Since the advertisement of a unilateral contract is generally open to the public at large and can be accepted by anyone who performs the act stipulated in the offer, this creates problems for offeror in terms of communication of the revocation. Therefore, the courts will waive the strict need for actual communication. Instead,the offeror must take a reasonable steps to bring the withdrawal to the attention of those persons who might be likely to accept, even though it may not be possible to ensure that they all know about it. Thus, in American case of Shuey v United States (1875) 92 US 73, it was held that an offer made by advertisement in a newspaper could be revoke by a similar advertisement, even though the second advertisement was not read by all the offerees.

Note:

In advertisement of unilateral contracts offeror may be able to revoke without the need for communication if the revocation take place before performance has began.